I got slammed by the start of Fall term, so I’m only now finding time to keep up my blog, but I have been reading some graphic novels.

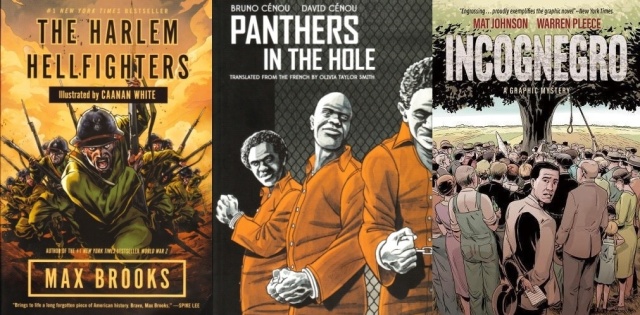

I’ve been trying to decide on a graphic novel to include in an African American literature class I’ll be teaching in the Winter term. Right now, I’m in the process of reviewing Harlem Hellfighters by Max Brooks & Caanan White and Panthers in the Hole by Bruno Cenou & David Cenou. Harlem Hellfighters is based on the true story of 369th Infantry Regiment of African American soldiers who served and fought in WWI. Panthers in the Hole is about the Angola Three (Robert King, Albert Woodfox, and Herman Wallace), who were members of Angola Prison’s chapter of the Black Panthers, and who each spent decades in solitary confinement.

In the case of the former, I’m wondering if the structure and handling of the story, including point of view, is literary enough given that it’s inclusion will knock out a more established piece of literature. Then there’s also the consideration that Max Brooks (the writer) isn’t African American, but Caanan White (the illustrator) is. What would be the politics of including a non-African American writer when the storytelling is as much in the visual rendering as it is in the plotting and writing? I’ll mull such questions over while finishing Brooks’ & Whites’ book.

The latter consideration is amplified in the case of Panthers in the Hole, which is written and illustrated by two French artists, but which tells a very important African American story. I do feel a responsibility to exposing students to the greatest breadth of actual African American writing as possible, so the only real pedagogical justification I can think for its inclusion would be to teach it at the end of the term and pose the question of African American authorship vs. African American story as a final essay project. At this point, I’m leaning toward just sharing an excerpt for discussion and just assigning a smaller response paper on the same question, but I’ll see how I feel once I finish the piece.

I thought about including the Octavia Butler graphic novel adaptation, Kindred, by Damien Duffy and John Jennings, but since I plan on teaching her original novel, Kindred, I think that pretty much excludes any such thoughts. If I were teaching on a semester system, I’d probably do it, but in a quarter system with 10 weeks to play with instead of 16, I think assigning both would be indulgent and detrimental to providing coverage of the breadth of African American literature.

What I would like to include is Mat Johnson’s & Warren Pleece’s Incognegro, which is about a light skinned African American journalist who is able to pass for white and who travels to the American south in the early 20th Century to investigate lynchings. It would fit in nicely with how I’m currently planning out the class, given that I’ll be teaching Mat Johnson’s Loving Day and Nella Larsen’s Passing, both of which deal with light vs. dark skin color and identity. However, Incognegro fell out of its initial publishing run and is not scheduled for republication until February, so do I really want to plan my syllabus around a book that isn’t even available yet? For example, what would I do if it were delayed a month or even beyond the Winter term?

If you have other recommendations, please share them in the comments.

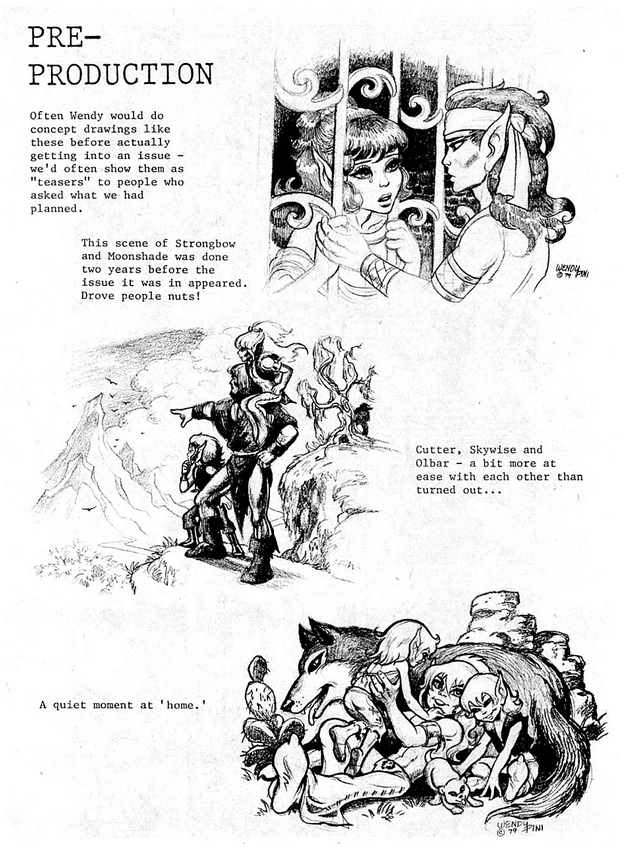

Also, I still have one or two more Wendy Pini posts that I had started working on before the start of Fall term knocked me off balance. I still plan to finish those and post them.