For Free Comic Book Day, I offer a review of Bart Beaty’s Comics versus Art, which is an excellent resource for anyone interested in the history of critical debates about the cultural place of comics.

Beaty begins by observing how comics are often taught as literature and expresses a desire to consider them more from a graphic perspective as art. As he notes, “[o]ne of the significant consequences of the literary turn in the study of comics has been a tendency to drive attention away from comics as a form of visual culture” (18). His desire to examine comics in relation to art pushes back against historical assertions by Sterling North, David Carrier, Reinhold Reitberger, Wolfgang Fuchs, and others that comics are not art. Beaty quotes Karl E. Fortress, who even goes so far as to state that “[t]he comic strip artist is not concerned with art problems, problems of form, spatial relationships, and the expressive movement of line. In fact, a concern with such problems would, in all probability, incapacitate the comic strip artist as such” (19). Over the course of Comics versus Art, Beaty presents example after example that undermines Fortress’ low placement of comics. Beaty seems to root his framework for the exclusion of comics from art in the five symbolic handicaps that Thierry Groensteen believes contribute to the devaluation of comics as a cultural form, in short; 1. being a bastard genre, 2. being juvenile in form an audience, 3. being associated with degraded forms like caricature, 4. the non-integration of comics into the visual arts, and 5. their mass production and tiny form. The placement of mass culture within the high/low hierarchy of the art world plays a big role in Beaty’s project. He argues that the diminution and disparagement of mass culture and with it a feminization (or emasculation) of comics vis-a-vis the proper (and therefore more masculine) field of the high arts sets up a gendered framework through which the contentious relationship between comics and art can be best understood.

Beaty then examines a range of formal definitions of comics that have been proposed by Martin Sheridan (1942), Colton Waugh (1947), David Kunzle (1973), Will Eisner (1985), M. Thomas Inge (1990), Scott McCloud (1993), R.C. Harvey (1994), Paul Sassienie (1994), Bill Blackbeard (1995). While this mostly seems like an offset for his eventual argument that understanding comics as art cannot rely upon formal definitions of comics but instead on the consideration of whether a comics art world has developed to validate comics as art, the excursion proves more interesting than mere contrast material. For example, he compares the national interests of the likes of Blackbeard, who would like to foster national claims of comics being a particularly American genre beginning with The Yellow Kid, with the art history approach of the likes of Kunzle and Sassienie, who would have us date comics back to cave drawings and tapestry work (though perhaps really taking formal shape with Rodolphe Topffer). Toward the end of this excursion, he credits McCloud with the most well known formal definition of comics, but takes him to task for its limitations:

While his attention to formal properties has helped to reorient discussion of comics away from their strictly social functions, McCloud’s overly expansive conception of “art” (“any human activity which doesn’t grow out of either of our species’ two basic instincts: survival and reproduction”) serves to obscure the aesthetic element of comics by regarding almost all human activities as art. (35)

In part, I find Beaty’s dismissal of the formal definition of comics to be a somewhat artificial maneuver to set up his own project of examining whether a comics art world has developed to affirm comics as art. However, he does offer a strong historical overview of the attempts at formal definitions that in and of itself can be a useful resource for the projects of others, so if it is a straw man it is a substantially filled one.

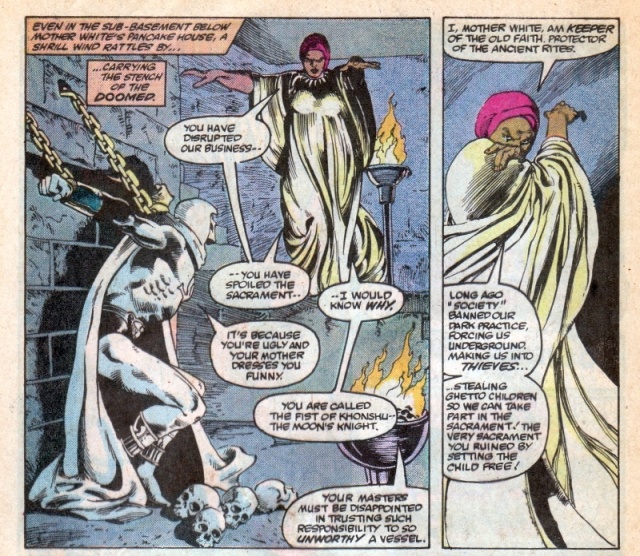

When Beaty launches into his comics art world project directly in Chapter Three, he starts off with the Nietzsche’s concept of ressentiment, which “suggests that, among subordinated peoples, the ego creates the illusion of an enemy that can be blamed for one’s inferiority, the rationalization that one has been thwarted by ‘evil’ forces, and the eventual creation of an ‘imaginary vengeance'” (52). It is in this context that Beaty argues that the comics world resents the art world as best manifested by the resentment many comics artists seem to feel toward Roy Lichtenstein, who rose to pop art fame by extracting individual frames from actual comics, enlarging them, making them more colorful via his treatment of them, and receiving high art acclaim for the sense of irony that he brought to the surface. Via Lichtenstein, comics became the raw cultural material from which “real” art could be made. The manifested resentment can perhaps be best summed up by a wartime story by cartoonist Irv Novick that Steve Duin and Mike Richardson relate in Comics between the Panels, from which Beaty quotes:

He had one curious encounter at camp. He dropped by the chief of staff’s quarters one night and found a young soldier sitting on a bunk, crying like a baby. “He said he was an artist,” Novick remembered, “and he had to do menial work, like cleaning up the officers’ quarters.

“It turned out to be Roy Lichtenstein. The work he showed me was rather poor and academic.” Feeling sorry for the kid, Novick got on the horn and got him a better job. “Later on, one of the first things he started copying was my work. He didn’t come into his own, doing things that were worthwhile, until he started doing things that were less academic than that. He was just making large copies of the cartoons I had drawn and painting them. (56)

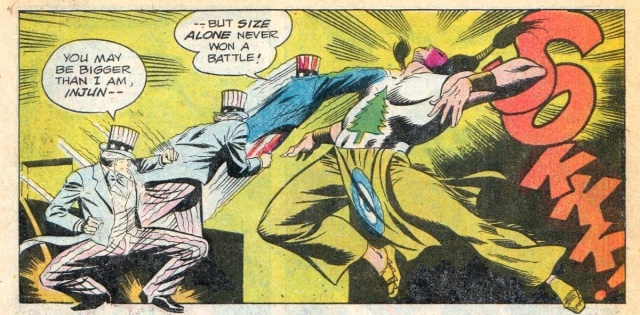

Beaty argues that Irv Novick, whose work only made its way into the art world via Lichtenstein’s “ironic” treatment, positions himself as the real man against Lichtenstein’s “crying like a baby” in order to try to reverse the way in which Lichtenstein’s fame and stature feminized comics and comic artists. He calls this a “crisis of masculinity” for comics posits that, contrary to claims by Andreas Huyssen that we’ve moved past the positioning of mass/commercial/popular culture as feminine and high culture as masculine, pop art’s relationship with comic books is one of gendered hierarchy: “It was clear, therefore, that Lichtenstein’s success stemmed, at least in part, from the association of his work with masculine–that is to say legitimated–values while his source material was held up as an example of the feminized traits in American (mass) culture that the artist had successfully recovered and repatriated.” (64). The irony that Lichtenstein’s work itself attempts to identify irony in traditional American gender roles is not lost on Beaty.

In ensuing chapters, Beaty looks for identifiable artists and masterpieces in the comics world. For example, in Chapter Four, after an interesting consideration of the public perception of the comics artist as represented in cinema via Artists and Models (1955) and How to Murder Your Wife (1965), he looks at the cases of Fletcher Hanks and Carl Barks, who could be identified as important cartoonists. While Beaty uses Hanks to pose the question of the thin distinction between naive art and comics art, his consideration of Barks is more expansive. Carl Barks was a Disney artist that the Disney studio did not credit but whose fans began to identify via his rendering of Donald Duck being distinct and better drawn than the rendering of other illustrators, enough so that the fans themselves eventually identified Barks as the artist. While not necessarily deeming Barks’ work to reach masterpiece status, Beaty holds this out as a turning point whereby a community of fans was able to recognize an artist and make his identity as an artist public. While Beaty spends much time discussing the role of fans in relation to the comics world and the development of a comics art world, I don’t think he ever fully resolves the implicit dichotomy of fans of comics versus patrons of the arts, itself a gendered component of his framework.

In the same chapter, he examines the artistic versus commercial battles of Jack “King” Kirby to own and possess his original works from Marvel, resulting in the return of just 1,900 out of 13,000 pieces for signing a waiver renouncing any claim to characters that he helped create. Beaty then considers in contrast the rise of Charles Schulz, who maintained full artistic and commercial licensing control over the Peanuts. What Beaty seems to find most interesting about Schulz is the way in which the comics world positions Schulz as perhaps the first great artist of the comics world. Nonetheless, the mantle seems to be an awkward one at best, for while The Complete Peanuts stands out as “a connoisseur’s product,” it seems “like an incongruous way to celibrate the work of a man who sold more than a million copies of a book titled Happiness Is a Warm Puppy” (95). Perhaps ironically, given his framework of the gender dichotomies surrounding high brow art and low brow or mass entertainment, Beaty never quite resolves within his own theorizing the mass-produced commercial aspect of comics that the art world itself seems to hold against the comics world.

In the remaining chapters, Beaty moves to identify comics masterpieces, the post-Lichtenstein debate of high versus low art in the formation of art objects and the role of collectibility (especially vis-a-vis Gary Panter) in the formation of a comics art world, and the place of comics in museum shows and exhibits. While George Herriman‘s Krazy Kat may be argued to be the first comics masterpiece and EC Comics may have offered masterpiece aesthetics, Beaty’s consideration of Robert Crumb and Art Spiegelman is especially worth calling out from the remainder of the book: “Comics Journal editor Gary Groth contrasted Spiegleman with Robert Crumb, citing the latter as a ‘landmark cartoonist,’ and the former as someone who has produced a ‘breakthrough work,’ which is to suggest that Spiegelman lacks Crumb’s natural drawing gifts but has, on the whole, produced a more significant piece upon which to hang his overall reputation” (117). In the context of Beaty’s gendered framework, Robert Crumb proves to be the defiant blue collar type man who rejects the high art world as corrupt at best and a big con at worst. As Crumb puts it, “I’m not interested in a bunch of cake eaters that go sniff around museums” (207). Meanwhile, Art Spiegelman via Maus proves to be the comics artist who achieves legitimation for himself and comics by producing what is arguably the first fully recognized masterpiece. This isn’t to say Crumb doesn’t have footing in high art, as his many showings in museums (documented by Beaty) would well attest to, but rather that Crumb even in finding acceptance rejects any need for validation, which for Beaty would be another form of ressentiment. Rather, via Spiegelman you can track a lineage from George Herriman’s Krazy Kat to Bernard Krigstein’s “Master Race” to Maus that may well elevate appreciation of the formal aesthetics of comics and what they’re capable of expressing in general. While Lichtenstein may have stood upon comics by highlighting their then perceived limitations, Spiegelman elevates them by showcasing their expressive capacity.

Perhaps also worth mentioning in Beaty’s project is Chapter Six, “Highbrow Comics and Lowbrow Art? The Shifiting Contexts of the Comics Art Object,” which examines the way in which the rise of publications like RAW and Blab! challenged the prejudices of kitsch and made comics into the low culture objects of choice for highbrows. For example, according to Beaty, RAW‘s selection of what to include or not to include in the way of comics art “allowed the editors to positon RAW within a particular comics lineage that was at once international, highly formalist, and, given the interests and reputation of mid-century cartoonists such as Wolverton, Rogers, and Hanks, irreverently outside the mainstream of American comics publishing” (135). Part of what RAW and Blab! did best was to create a space for comics art that sat alongside but separate from the central commercial models of publishing. Perhaps a shortcoming is that Beaty doesn’t really consider the gendering of this space given his larger framework.

In his final chapter, Beaty acknowledges that the book is difficult to conclude as the “legitimating process that comics are involved in remains very much ongoing” (212). However, in way of offering a conclusion he focuses on the work and place of Chris Ware, who serves as a significant and necessary bridge between the comics world and the high art world:

Insofar as he so perfectly occupies the space allotted to a cartoonist in the art world at this particular moment in time–innovatively cutting edge in formal terms, technically brilliant as a designer and draftsman, but viciously self deprecating in his willingness to occupy a diminished position in the field, strongly masculinist in his thematic concerns and aesthetic interests, and willfully ironic about the relationship between comics and art in a way that serves to mockingly reinforce, rather than challenge, existing power inequities–it can be said that if Chris Ware did not exist, the art world would have to invent him. (226)

I don’t know whether that last creative turn of phrase, suggesting that we’ve arrived at a point where the art world has need of the comics world and its artists, does enough to fulfill the promising theoretical framework with which Beaty sets out his project. And the insertion of “masculinist” there certainly feels more artificial than an organic part of his gendering critique. However, the sum of its parts (many of which I haven’t even touched on in this blog post, like the effect of attempting to censor comic books in the mid 20th Century) makes Comics versus Art well worth the read.

Drawing made by a student during daily start of class assignment.

Drawing made by a student during daily start of class assignment.