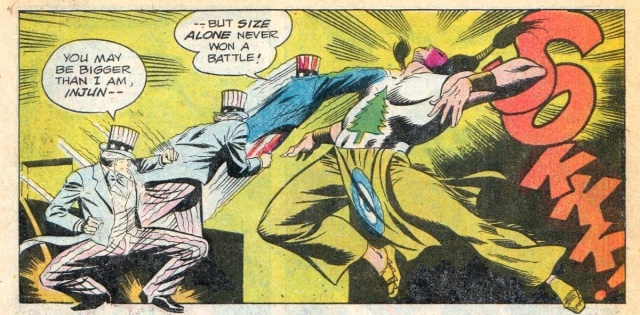

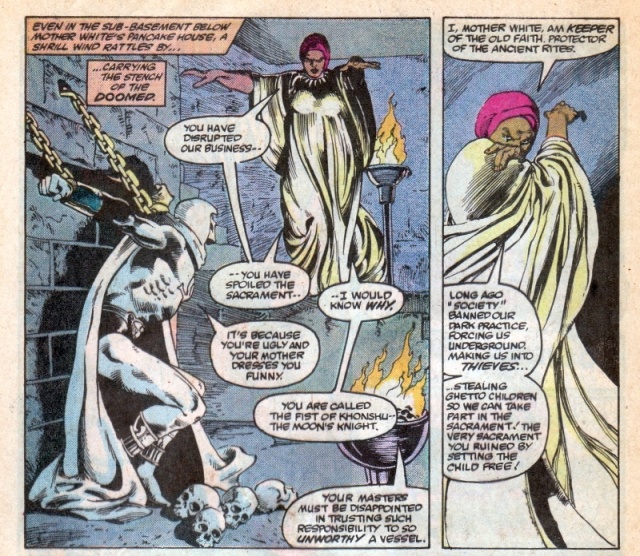

Covers from Freedom Fighters (1977) and Moon Knight (1985)

I don’t recall seeing an Asian character playing a central role in a comic book until my mother took me to some kind of expo and purchased for me a WWII comic book that followed the story of a Japanese naval officer during and after the Battle of Midway. It wasn’t until I was older that I realized what I had read was a form of religious propaganda, with the Japanese soldier eventually recognizing the might of American military power and after the war finding grace in a Christian God (these two things no doubt intended to serve as analogs for one another). I think I threw it away when I was in college, but I now find myself wishing I had held onto it. I did, however, hang on to the Freedom Fighters and Moon Knight issues you see above. Both offer examples of the problematic relationship comic books have historically had with race.

Freedom Fighters was probably one of those comic books my mom kindly bought for me while checking out at the store. In the #11 issue, a group of Native Americans con people out of money by pretending to ask for donations for a fake school. Tired of meager scraps, they call upon their ancestors and receive mystical intervention in the form of super powers that they then use to commit more lucrative crimes. The eponymous Freedom Fighters, led by the heroic and patriotic Uncle Sam, have to stop the now villainous Renegades. Captured by the Freedom Fighters and served up to the police in the end, one of the Renegades says, “We should be freed also — we were merely furthering our cause — righting wrongs done years ago,” to which the arresting officer replies, “Mister, your ‘cause’ seems to go only so far as your pocket!” This issue was published six years after the Occupation of Alcatraz and in the same year as Leonard Peltier‘s conviction, neither of which I had any real sense of as a kid.

In the #6 issue of Moon Knight, Marc Spector is a superhero attired ostensibly in a white hood and a white costume (supposedly the costume is meant to be silver but comes off to my eyes as white), struggling against tragic odds to save Blacks from the corruption and drugs perpetrated upon them by their own leaders: a heroin addicted U.S. government agent and a fanged voodoo priestess. I think it does little to deflect the racial history of white hoods and costumes and the representation of Black communities as corrupt and self-destructive that an early line deposits this story in the Caribbean. The white hooded hero as rendered in this issue brings to my mind of D.W. Griffith’s valorization of the KKK in The Birth of a Nation (1915), though I’m sure in other issues Moon Knight has some other less racially charged adventures.

Perhaps luck would have it that I managed to hang onto two of the more extreme examples for racial representations in comic books, but I can’t say as I can recall much more positive and recurring images of Native Americans or African Americans. Sure, there were Apache Chief in the cartoons and Luke Cage in the comics, neither an unproblematic representation of ethnic others, but perhaps more damaging is the lack of a range of images and with such range a continuous presence. And, as noted above, there was also the absence of Asian American characters (or at least none that I recall reading when I was growing up), which is what makes Gene Luen Yang, Sonny Liew and Janice Chiang’s The Shadow Hero (2014) an interesting and compelling story today. In The Shadow Hero, Yang, Liew, and Chiang offer an origin narrative of sorts for the hero of Chu Hing’s 1940s series, The Green Turtle. They argue that Chu Hing wanted his hero to be Chinese and that the dearth of clear shots of the hero’s face was his way of getting around publishers who wanted the hero to be white, situating a Chinese representation in the absence of a clear face determining otherwise.

As a final note, I don’t recall owning any comic books with Chicano/a or Latino/a super heroes, either.

Drawing made by a student during daily start of class assignment.

Drawing made by a student during daily start of class assignment.